Origin and perspective of Spanglish (II)

Inglanol, espanglés, bastard Spanish, Pachuco slang, pocho and many others, have been terms utilized for long time almost as a reproach related to the existence of a mutilated and mended language, to the illegitimate mixture of two tongues, to what today is known as Spanglish and which, by spreading as an inevitable practice due to the interaction of biculturalism in the United States, has now earned the right of proclaiming its existence.

Despite the fact that these days “Spanglish” is the most popular utilized term and that its philological composition is easy to decipher (Spanish + English); discovering where and how the rest of the terms used to refer to this hybrid came from, has become an arduous task, even when we recur to its etymology.

For instance, the root of the word pachuco is attributed to the náhuatl dialect: Pachuco (náhuatl pachoacan [place to govern]). Other voices sustain that ‘Pachuco’ is a mutation of the word ‘pocho,’ an expression utilized for decades both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border; although several studies on the subject make a solid differentiation between the two terms.

According to studies conducted by the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, the term pocho appears publicly during the 1920s. This information is included on the Chicano Satire1 essay, by Guillermo E Hernandez.

“The term pocho appears as a publicly recognized label in Chicano books, newspapers, theatrical revues, and songs during the 1920s. Its usage assumes a tacit understanding of its meaning by a wide audience, thus suggesting its probable employment at an informal level for some time before.

Most of the evidence we have from this period is found in the immigrant press that flourished in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution.”

“An early use of the term pocho appears associated with Californians whose cultural traits were judged to be heavily influenced by Anglo-American language and life-style. But it also was applied to individuals of Mexican rural origin who awkwardly imitated Anglo-American linguistic conventions. Arnold R. Rojas, discussing the language of Californians in the nineteenth century, suggests that the word may be of Indian origin: “About the only Indian word (said to be derived from the Yaqui (Sonora state in Mexico —and that is debatable) is pochi (…) Californians became ‘pochos’ or ‘pochis’ when Alta California was severed from Mexico”

In accordance with Hernandez’ essay, a fuller treatment of the origin of the word, of what it means to be, and to ‘talk’ pocho, is found in the columns entitled “Crónicas diabólicas” (Diabolic chronicles) by Jorge Ulica (Julio G. Arce) published in the newspaper Hispano América in San Francisco between 1916 and 1926. With headlines as “Do You Speak pocho?” “Los parladores de Spanish,” and “No hay que hablar en pocho,” Ulica satirizes the naive immigrant of rural origin who mixes Anglicisms with dialectal expressions and awkwardly adopts the customs of Anglo-Americans.”

Ulica wrote:

“El pocho se está extendiendo de una manera alarmante. Me refiero al dialecto que hablan muchos de los “Spanish” que vienen a California y que es un revoltijo, cada día más enredado, de palabras españolas, vocablos ingleses, expresiones populares y terrible “slang.”

De seguir las cosas así, va a ser necesario fundar una Academia y publicar un diccionario español-pocho, a fin de entendernos con los nuestros. (Crónicas diabólicas 153)

[pocho is disseminating in a manner that causes alarm. I am referring to the dialect spoken by many of the “Spanish” that arrive in California and which consists of a mixture, every day more confusing, of Spanish words, English vocabulary, popular expressions, and awful “slang.”

Should things continue like this, it will become necessary to open a school and to publish a Spanish-pocho dictionary in order to communicate with our own people.]

And it seems like Ilan Stavans2 took Ulica’s old wish, as a command. In 2003, this writer and university professor published the book Spanglish: The Making of a New American Language, which includes a vocabulary of approximately 6,000 Spanglish words and additionally, he translated into Spanglish the first chapter of Don Quijote de la Mancha.

For Stavans, who currently teaches a Spanglish course as part of the curriculum of the Amherst College in Massachusetts, Spanglish has been an underground vehicle of communication in the U.S. for over 150 years, which has gained momentum during the last two decades. On his critical essay Spanglish: Tickling the Tongue, he says:

“Spanglish is not only a form of code switching; it is an altogether fresh tongue.” To linguists and intellectuals who oppose the recognition of it even as a sub-tongue, Stavans says:

“I am not at all surprised that the dissemination of Spanglish in the United States has given way to an atmosphere of anxiety and even xenophobia in both Hispanic and Anglo enclaves. In the United States, its impact announces an overall hispanizacion of the entire society, whereas in the Americas it generates fear that the region’s tongue, seen by many as the last bastion of cultural pride, is being taken over by American imperialism.”

Rita Cano Alcalá3, Associate Professor of Hispanic Studies and Chicano Studies at Scripps College in Claremont, narrates how the existence of discrimination for speaking Spanish in this country, is something that she learned during her childhood.

“My personal experience as a chicana was very peculiar; in my house, we tried to maintain a correct Spanish. But being chicanos, my Mexican-American parents didn’t have a very sophisticated vocabulary,” says Alcalá in conversation with hispanicLA.

“When I signed up in college, I decided to study Spanish because I had never had the opportunity of learning it correctly…all the Spanish I knew from an original source came from the letters I used to write to my grandmother (in Mexico).”

The persisting stigma among chicanos -which once also existed toward pachucos– created the tendency for which “not all chicanos refer to themselves as chicanos,” says this passionate linguist.

“Pachucos are a generation that has survived through ‘cholos’ whom at the same time have included many words from that slang in their lexicon. There is a linguistic overlap between them.”

Alcalá, as other scholars, finds an outstanding difference between the Spanish that arrived to this country with her parent’s generation, which included words common to rural environments such as ‘trujo’ (correct word = trajo / brought); and the lexicon utilized by Pachucos, which included words as ‘tira’ (correct word = camisa / shirt), or ‘ruca’ (correct word = mujer / woman).

“The linguistic formation during the period 1930 – 1950 created a bicultural environment on which parents would do extraordinary efforts to preserve their original culture, already immerse on the local popular way of life, while being extremely discriminated. But then, they (Pachucos) took ownership of that culture in the creation of that jargon and slang. And this is a very particular aspect of the lexicon that is a part of the Spanglish we know today, but we cannot say that [the Spanglish of pachucos, of cholos and the one we hear today] is the same thing.”

Retrospective

California in general and Los Angeles in particular have been historically associated with a tradition of biculturalism whose existence is known since the first half of the Nineteenth Century, when the United States expropriated one half of Mexico’s territory; and from the Twentieth Century, with the massive migrations after the Mexican Revolution and of the Bracero Program. These can be named as the very first events that caused a partial ethnic re-composition of the U.S. and propelled a growing linguistic English-Spanish fusion.

Whereas during the 1950s Hispanics timidly approach the fight for civil rights, during the 1960s they openly reveal their presence in this country. The Mexican-American communities in California and in Texas gave origin to the Chicano Movement4, which was turned into a resistance movement advocating for the rights of the whole Latino community. That’s how leaders as Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez emerge to create the United Farm Workers (UFW), based in the Central Valley of California. Spanish continues to be alive in those clusters, while it carries on its own process of transformation.

The Hispanic communities joined the activism across the country and simultaneously, triggered the reconfiguration of the United States. New York attracted Puerto Rican immigrants with its causes, while Florida did the same with Cubans.

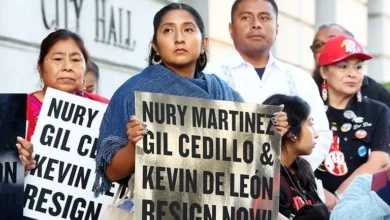

Between 1970 and 1990 the civil wars in Guatemala, El Salvador and Nicaragua produced a strong migratory wave arriving from Central America; and by 1980, it accelerated the transformation of Latinos into a visible group, due to the noticeable increase of its population. In the scenario of the national economy they represented by then, a significant force: politicians of Hispanic ascend started to move up in rank and hierarchy. They would address their Hispanic audiences in Spanish, or better said, in Spanglish.

By 2004, population of Hispanic origin outnumbered African-Americans as the most numerous minority in this country. The current figure of 47 million Hispanics6 in the United States, translates into a significant force of influence in the economy, politics, education and in social and cultural affairs.

The Spanish language and its multiple shades, including its partial fusion with English –purpose of this analysis- constitutes an individual form of expression in itself: undeniable and unstoppable.

Perspective

The dialectological profile of the Spanish that is spoken and -more recently- written in the United States, has been configured by the migratory flows emerged from specific areas of what we know as Hispanic-America. Each of such linguistic groups has contributed to the Spanish and the Spanglish we know today and that inexorably, will continue its evolving process.

Such evolution is at the same time, impacted by the influence that those groups have experienced by their contact with Anglo-Hispanic bilingualism, which is characteristic of a big percentage of Spanish speaking people, born or raised in this country. In that sense, there is a general perception that the different ‘types’ of Spanish imported by immigrants start turning into hybrids, as a result of the communicative activity of those whom, -individually or in group- think in Spanish at the time they speak in English; or those who, inversely, think in English and find themselves in the need of speaking in Spanish.

There is nothing new in regards of the continuous lexicon loans from English to Spanish, and vice versa; the innovative element is precisely the permanent and growing melting pot, in which this country has been transformed by allowing a significant level of sociolinguistic integration of the Hispanic communities that have arrived to stay.

Spanglish detractors point out, it represents the decomposition of the Spanish grammatical -and even phonological- system, according to English patterns [let’s remember the tendency of adding Spanish infinitive suffixes, to verbs originally in English, as on: to park: + estacionar = park+ ar = parkiar] in such manner that, we are forced to admit the possibility of a partial and eventual transformation of a ‘pure’ bilingualism, into a bivalent-type of hybrid, in the long term.

Other angle to attack Spanglish finds its pretext in the association that is done of it, with the pauper, whose notoriety became more evident through the years, in street expressions of East L.A.’s cholos and gangs; however, there has been a change also in those stereotypes.

In other words, we cannot continue to accuse Spanglish of being a street lingo. In recent years, the profile of an important percentage of Hispanic immigrants who have arrived to the United States, has changed: not only they come here legally, but additionally, they arrive possessing a higher level of education. Many of them are already bilingual, so they don’t come to learn English here, although they show a tendency to acquire the local slang and with it, they show proclivity to also speak in Spanglish.

At the same time, the third and fourth generation of Hispanics, tend to finish their college level education. Many of them preserve the language of their parents or grandparents, recurring in one way or another, to Spanglish as a communication tool. The trajectory of these new groups from Hispanic descend break up with the traditional stereotype and expands the spectrum of those who utilize Spanglish frequently, and the way they do it.

Ilan Stavans also touches this aspect in his essay Spanglish: Tickling the Tongue.

“Spanglish (…) is not defined by class, for people in all social strata, from migrant workers to upper-class types such as congressmen, TV anchors, and comedians, use it regularly. South of the Rio Grande, Spanglish also knows no boundaries as it permeates all levels of the socioeconomic system.”

In that sense, Rita Cano Alcalá affirms that, in linguistic terms and despite its adversaries, nowadays there is a better acceptance of Spanglish. Not only due to its adoption by Hispanics with a higher education or socio-economic level, but due to the fact that the linguistic universe of technicisms has been put to the disposition of the whole world throughout the internet, where the names of new technologies are adopted by hundreds of languages, which makes the fusion of such terms –generally in English- in our case with Spanish, something more frequent and acceptable.

“At the same time there is a worldwide aspect of Spanglish with technology, and now there is more acceptance from English terms to Spanish. For instance, people do not judge the use of the word ‘web’ anymore, since is one of the most accepted terms and is not seen as ‘language corruption.’”

That way, we definitely see that there is not only one kind of Spanglish, but that its evolution it’s being enriched by contributions originated in factors as nationality, age groups, educational level, social class and even technological advances.

Meaning, if at this point there is a ‘universal’ Spanglish for all Spanish speakers, it is also important to recognize that the Miami’s Cuban-Americans lingo is different from the New Yorkers’ Spanglish and at the same time different form the one spoken at East Los Angles. The generational distinctions also take a relevant role in the practical evolution on this sub-tongue.

In honor to those devastating the presence of Spanglish in the U.S., it is valid to recognize that, certainly, cultures are comprised of, and achieve their identity trough different components, and that, one of the most relevant, indeed is, the existence of a common tongue. Nevertheless, the political division that demarcates nations geographically, along with their culture and their language, has demonstrated that there is an exception to the rule. There we have the case of Switzerland7, a country with four official languages spoken throughout its territory: German [74%], French [21%], Italian [4%] and Rumantsch [1%]. With it, we are not suggesting that Spanish –or even in a near future Spanglish- should be adopted as an official second language or a sub-tongue in the United States. At least, not yet. What we are attempting to suggest is that the harmonic coexistence of two or more official languages is possible in one country. Without going any further, we also have the case of Canada8, where English [67%] is as official as French [21.5%].

Now, the question before both the American and the Hispanic culture should be: does Spanglish bring us together, or does it divide us? Paraphrasing the great Octavio Paz in one of the stories of The Labyrinth of Solitude, also appears the question: “one language or two?” “What can we offer from our own otherness to each other and to the rest of the world, particularly in our century when the encounter or the reencounter between us seems to be inevitable?” And as Paz, we also ask ourselves if it is indeed possible that borders can cease being a limit and a limitation, to be transformed in a point of reunion, of communication within us.

Ilan Stavans is right when he criticizes left-wing militants in Latin America who believe they have to do ‘something’ to counterattack the arrival and influence of Spanglish and they scream “¡Muera Hollywood!”, “¡Muera el espanglés!”; while this side of the border, right-wing opponents fear that their own nation is in the course of an aggressive decline that will bring an inevitable switching of tongues. Furthermore, Stavans cannot be more certain than when he says:

“But a language cannot be legislated; it is the freest, most democratic form of expression of the human spirit. And so, every attack against it serves as a stimulus, for nothing is more inviting than that which is forbidden.”*

Notes:

1. Chicano Satire. Essay by Guillermo E Hernández, Professor of UCLA Spanish and Portuguese Department and UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

2. Ilan Stavans. Professor, critic, linguist, translator, lecturer, editor, writer, and TV presenter, his most prominent work is centered in the study of language, identity, politics and history. He was born in Mexico City in 1961, to a Jewish family with roots in Eastern Europe.

3. Rita Cano Alcalá. Associate Professor of Hispanic Studies and Chicano Studies at Scripps College, Claremont, CA.

4. Chicano Movement.

5. United Farm Workers of America, UFW.

6. U.S. Census Bureau. General Demographic Characteristics: July 2008. (Updated to 2008).

7. Switzerland oficial languages.

Origin and perspective of Spanglish (II)

Inglanol, espanglés, bastard Spanish, Pachuco slang, pocho and many others, have been terms utilized for long time almost as a reproach related to the existence of a mutilated and mended language, to the illegitimate mixture of two tongues, to what today is known as Spanglish and which, by spreading as an inevitable practice due to the interaction of biculturalism in the United States, has now earned the right of proclaiming its existence.

Despite the fact that these days “Spanglish” is the most popular utilized term and that its philological composition is easy to decipher (Spanish + English); discovering where and how the rest of the terms used to refer to this hybrid came from, has become an arduous task, even when we recur to its etymology. For instance, the root of the word pachuco is attributed to the náhuatl dialect: Pachuco (náhuatl pachoacan [place to govern]). Other voices sustain that ‘Pachuco’ is a mutation of the word ‘pocho,’ an expression utilized for decades both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border; although several studies on the subject make a solid differentiation between the two terms.

According to studies conducted by the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, the term pocho appears publicly during the 1920s. This information is included on the Chicano Satire1 essay, by Guillermo E Hernandez.

“The term pocho appears as a publicly recognized label in Chicano books, newspapers, theatrical revues, and songs during the 1920s. Its usage assumes a tacit understanding of its meaning by a wide audience, thus suggesting its probable employment at an informal level for some time before. Most of the evidence we have from this period is found in the immigrant press that flourished in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution.”

“An early use of the term pocho appears associated with Californians whose cultural traits were judged to be heavily influenced by Anglo-American language and life-style. But it also was applied to individuals of Mexican rural origin who awkwardly imitated Anglo-American linguistic conventions. Arnold R. Rojas, discussing the language of Californians in the nineteenth century, suggests that the word may be of Indian origin: “About the only Indian word (said to be derived from the Yaqui (Sonora state in Mexico —and that is debatable) is pochi (…) Californians became ‘pochos’ or ‘pochis’ when Alta California was severed from Mexico”

In accordance with Hernandez’ essay, a fuller treatment of the origin of the word, of what it means to be, and to ‘talk’ pocho, is found in the columns entitled “Crónicas diabólicas” (Diabolic chronicles) by Jorge Ulica (Julio G. Arce) published in the newspaper Hispano América in San Francisco between 1916 and 1926. With headlines as “Do You Speak pocho?” “Los parladores de Spanish,” and “No hay que hablar en pocho, “Ulica satirizes the naive immigrant of rural origin who mixes Anglicisms with dialectal expressions and awkwardly adopts the customs of Anglo-Americans.”

Ulica wrote:

“El pocho se está extendiendo de una manera alarmante. Me refiero al dialecto que hablan muchos de los “Spanish” que vienen a California y que es un revoltijo, cada día más enredado, de palabras españolas, vocablos ingleses, expresiones populares y terrible “slang.”

De seguir las cosas así, va a ser necesario fundar una Academia y publicar un diccionario español-pocho, a fin de entendernos con los nuestros. (Crónicas diabólicas 153)

[pocho is disseminating in a manner that causes alarm. I am referring to the dialect spoken by many of the “Spanish” that arrive in California and which consists of a mixture, every day more confusing, of Spanish words, English vocabulary, popular expressions, and awful “slang.”

Should things continue like this, it will become necessary to open a school and to publish a Spanish-pocho dictionary in order to communicate with our own people.]

And it seems like Ilan Stavans2 took Ulica’s old wish, as a command. In 2003, this writer and university professor published the book Spanglish: The Making of a New American Language, which includes a vocabulary of approximately 6,000 Spanglish words and additionally, he translated into Spanglish the first chapter of Don Quijote de la Mancha.

For Stavans, who currently teaches a Spanglish course as part of the curriculum of the Amherst College in Massachusetts, Spanglish has been an underground vehicle of communication in the U.S. for over 150 years, which has gained momentum during the last two decades. On his critical essay Spanglish: Tickling the Tongue, he says:

“Spanglish is not only a form of code switching; it is an altogether fresh tongue.” To linguists and intellectuals who oppose the recognition of it even as a sub-tongue, Stavans says:

“I am not at all surprised that the dissemination of Spanglish in the United States has given way to an atmosphere of anxiety and even xenophobia in both Hispanic and Anglo enclaves. In the United States, its impact announces an overall hispanizacion of the entire society, whereas in the Americas it generates fear that the region’s tongue, seen by many as the last bastion of cultural pride, is being taken over by American imperialism.”

Rita Cano Alcalá3, Associate Professor of Hispanic Studies and Chicano Studies at Scripps College in Claremont, narrates how the existence of discrimination for speaking Spanish in this country, is something that she learned during her childhood.

“My personal experience as a chicana was very peculiar; in my house, we tried to maintain a correct Spanish. But being chicanos, my Mexican-American parents didn’t have a very sophisticated vocabulary,” says Alcalá in conversation with hispanicLA.

“When I signed up in college, I decided to study Spanish because I had never had the opportunity of learning it correctly…all the Spanish I knew from an original source came from the letters I used to write to my grandmother (in Mexico).”

The persisting stigma among chicanos -which once also existed toward pachucos– created the tendency for which “not all chicanos refer to themselves as chicanos,” says this passionate linguist.

“Pachucos are a generation that has survived through ‘cholos’ whom at the same time have included many words from that slang in their lexicon. There is a linguistic overlap between them.”

Alcalá, as other scholars, finds an outstanding difference between the Spanish that arrived to this country with her parent’s generation, which included words common to rural environments such as ‘trujo’ (correct word = trajo / brought); and the lexicon utilized by Pachucos, which included words as ‘tira’ (correct word = camisa / shirt), or ‘ruca’ (correct word = mujer / woman).

“The linguistic formation during the period 1930 – 1950 created a bicultural environment on which parents would do extraordinary efforts to preserve their original culture, already immerse on the local popular way of life, while being extremely discriminated. But then, they (Pachucos) took ownership of that culture in the creation of that jargon and slang. And this is a very particular aspect of the lexicon that is a part of the Spanglish we know today, but we cannot say that [the Spanglish of pachucos, of cholos and the one we hear today] is the same thing.”

Retrospective

California in general and Los Angeles in particular have been historically associated with a tradition of biculturalism whose existence is known since the first half of the Nineteenth Century, when the United States expropriated one half of Mexico’s territory; and from the Twentieth Century, with the massive migrations after the Mexican Revolution and of the Bracero Program. These can be named as the very first events that caused a partial ethnic re-composition of the U.S. and propelled a growing linguistic English-Spanish fusion.

Whereas during the 1950s Hispanics timidly approach the fight for civil rights; during the 1960s they openly reveal their presence in this country. The Mexican-American communities in California and in Texas gave origin to the Chicano Movement4, which was turned into a resistance movement advocating for the rights of the whole Latino community. That’s how leaders as Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez emerge to create the United Farm Workers (UFW), based in the Central Valley of California. Spanish continues to be alive in those clusters, while it carries on its own process of transformation.

The Hispanic communities joined the activism across the country and simultaneously, triggered the reconfiguration of the United States. New York attracted Puerto Rican immigrants with its causes, while Florida did the same with Cubans.

Between 1970 and 1990 the civil wars in Guatemala, El Salvador and Nicaragua produced a strong migratory wave arriving from Central America; and by 1980, it accelerated the transformation of Latinos into a visible group, due to the noticeable increase of its population. In the scenario of the national economy they represented by then, a significant force: politicians of Hispanic ascend started to move up in rank and hierarchy. They would address their Hispanic audiences in Spanish, or better said, in Spanglish.

By 2004, population of Hispanic origin outnumbered African-Americans as the most numerous minority in this country. The current figure of 47 million Hispanics6 in the United States, translates into a significant force of influence in the economy, politics, education and in social and cultural affairs.

The Spanish language and its multiple shades, including its partial fusion with English –purpose of this analysis- constitutes an individual form of expression in itself: undeniable and unstoppable.

Perspective

The dialectological profile of the Spanish that is spoken and –more recently- written in the United States, has been configured by the migratory flows emerged from specific areas of what we know as Hispanic–America. Each of such linguistic groups has contributed to the Spanish and the Spanglish we know today and that inexorably, will continue its evolving process.

Such evolution is at the same time, impacted by the influence that those groups have experienced by their contact with Anglo-Hispanic bilingualism, which is characteristic of a big percentage of Spanish speaking people, born or raised in this country. In that sense, there is a general perception that the different ‘types’ of Spanish imported by immigrants start turning into hybrids, as a result of the communicative activity of those whom, -individually or in group- think in Spanish at the time they speak in English; or those who, inversely, think in English and find themselves in the need of speaking in Spanish.

There is nothing new in regards of the continuous lexicon loans from English to Spanish, and vice versa; the innovative element is precisely the permanent and growing melting pot, in which this country has been transformed by allowing a significant level of sociolinguistic integration of the Hispanic communities that have arrived to stay.

Spanglish detractors point out, it represents the decomposition of the Spanish grammatical –and even phonological– system, according to English patterns [let’s remember the tendency of adding Spanish infinitive suffixes, to verbs originally in English, as on: to park: + estacionar = park+ ar = parkiar] in such manner that, we are forced to admit the possibility of a partial and eventual transformation of a ‘pure’ bilingualism, into a bivalent-type of hybrid, in the long term.

Other angle to attack Spanglish finds its pretext in the association that is done of it, with the pauper, whose notoriety became more evident through the years, in street expressions of East L.A.’s cholos and gangs; however, there has been a change also in those stereotypes.

In other words, we cannot continue to accuse Spanglish of being a street lingo. In recent years, the profile of an important percentage of Hispanic immigrants who have arrived to the United States, has changed: not only they come here legally, but additionally, they arrive possessing a higher level of education. Many of them are already bilingual, so they don’t come to learn English here, although they show a tendency to acquire the local slang and with it, they show proclivity to also speak in Spanglish.

At the same time, the third and fourth generation of Hispanics, tend to finish their college level education. Many of them preserve the language of their parents or grandparents, recurring in one way or another, to Spanglish as a communication tool. The trajectory of these new groups from Hispanic descend break up with the traditional stereotype and expands the spectrum of those who utilize Spanglish frequently, and the way they do it.

Ilan Stavans also touches this aspect in his essay Spanglish: Tickling the Tongue.

“Spanglish (…) is not defined by class, for people in all social strata, from migrant workers to upper-class types such as congressmen, TV anchors, and comedians, use it regularly. South of the Rio Grande, Spanglish also knows no boundaries as it permeates all levels of the socioeconomic system.”

In that sense, Rita Cano Alcalá affirms that, in linguistic terms and despite its adversaries, nowadays there is a better acceptance of Spanglish. Not only due to its adoption by Hispanics with a higher education or socio-economic level, but due to the fact that the linguistic universe of technicisms has been put to the disposition of the whole world throughout the internet, where the names of new technologies are adopted by hundreds of languages, which makes the fusion of such terms –generally in English- in our case with Spanish, something more frequent and acceptable.

“At the same time there is a worldwide aspect of Spanglish with technology, and now there is more acceptance from English terms to Spanish. For instance, people do not judge the use of the word ‘web’ anymore, since is one of the most accepted terms and is not seen as ‘language corruption.’”

That way, we definitely see that there is not only one kind of Spanglish, but that its evolution it’s being enriched by contributions originated in factors as nationality, age groups, educational level, social class and even technological advances.

Meaning, if at this point there is a ‘universal’ Spanglish for all Spanish speakers, it is also important to recognize that the Miami’s Cuban-Americans lingo is different from the New Yorkers’ Spanglish and at the same time different form the one spoken at East Los Angles. The generational distinctions also take a relevant role in the practical evolution on this sub-tongue.

In honor to those devastating the presence of Spanglish in the U.S., it is valid to recognize that, certainly, cultures are comprised of, and achieve their identity trough different components, and that, one of the most relevant, indeed is, the existence of a common tongue. Nevertheless, the political division that demarcates nations geographically, along with their culture and their language, has demonstrated that there is an exception to the rule. There we have the case of Switzerland7, a country with four official languages spoken throughout its territory: German [74%], French [21%], Italian [4%] and Rumantsch [1%]. With it, we are not suggesting that Spanish –or even in a near future Spanglish- should be adopted as an official second language or a sub-tongue in the United States. At least, not yet. What we are attempting to suggest is that the harmonic coexistence of two or more official languages is possible in one country. Without going any further, we also have the case of Canada8, where English [67%] is as official as French [21.5%].

Now, the question before both the American and the Hispanic culture should be: does Spanglish bring us together, or does it divide us? Paraphrasing the great Octavio Paz in one of the stories of The Labyrinth of Solitude, also appears the question: “one language or two?” “What can we offer from our own otherness to each other and to the rest of the world, particularly in our century when the encounter or the reencounter between us seems to be inevitable?” And as Paz, we also ask ourselves if it is indeed possible that borders can cease being a limit and a limitation, to be transformed in a point of reunion, of communication within us.

Ilan Stavans is right when he criticizes left-wing militants in Latin America who believe they have to do ‘something’ to counterattack the arrival and influence of Spanglish and they scream “¡Muera Hollywood!”, “¡Muera el espanglés!”; while this side of the border, right-wing opponents fear that their own nation is in the course of an aggressive decline that will bring an inevitable switching of tongues. Furthermore, Stavans cannot be more certain than when he says:

“But a language cannot be legislated; it is the freest, most democratic form of expression of the human spirit. And so, every attack against it serves as a stimulus, for nothing is more inviting than that which is forbidden.”

Notes:

1. Chicano Satire. Essay by Guillermo E Hernández, Professor of UCLA Spanish and Portuguese Department and UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

2. Ilan Stavans. Professor, critic, linguist, translator, lecturer, editor, writer, and TV presenter, his most prominent work is centered in the study of language, identity, politics and history. He was born in Mexico City in 1961, to a Jewish family with roots in Eastern Europe.

3. Rita Cano Alcalá. Associate Professor of Hispanic Studies and Chicano Studies at Scripps College, Claremont, CA.

4. Chicano Movement.

5. United Farm Workers of America, UFW.

6. U.S. Census Bureau. General Demographic Characteristics: July 2008. (Updated to 2008).

7. Switzerland oficial languages.